|

|

||||||||||

Military Operations - Militere Operasies

|

Operasie Savannah (1975 - 1976) In 1974 was die einde van die Portugese bewind in Angola reeds in sig. Die onstabiele veiligheidsituasie in Angola en die bedreiging wat die Angolese Burgeroorlog vir SWA ingehou het, het gelei tot die ontplooiing van 'n Suid-Afrikaanse beskermingsmag van slegs sowat 2 000 man in SWA se noordelike grensgebied. Hierdie mag, wat die FNLA en UNITA ondersteun het, het te staan gekom teen 'n groot oormag van Kubaanse en MPLA-magte, maar het desondanks skitterende oorwinnings behaal. In 'n Blitzkrieg het Taakmag Zulu die suidwestelike hoek van Angola herower nadat Perreira de Eca, Rocades en verskeie ander dorpe ingeneem is. In Sentraal-Angola het Veggroep Foxbat in Oktober 1975 die vyand by Liurnbala verslaan. Hierna het Taakmag Zulu verdere oorwinnings by Cacula en Catengue behaal. Die oorwinnings by Catengue in November 1975 het die vyand gedwing om die Benguela-front te ontruim. Taakmag Zulu en Veggroep Foxbat het die vyand in die Santa Comba-gebied aan die Cela-front, gestuit en 'n oorwinning in die slag van Ebo behaal. In die ooste van Angola het Veggroep X-Ray (later herdoop tot Veggroep Orange) ook oorwinnings by Xangongo en Lusp behaal. Taakmag Zulu en Veggroep Foxbat se oorwinning by die slag van Brug 14 aan die sentrale front is wel bekend. Die slag het plaasgevind nadat die Suid-Afrikaanse magte na Quibala opgeruk het. Hulle moes egter die Nhiarivier by Brug 14 (wat deur die vyandelike magte vernietig is) oorsteek en hier het die genietroep te midde van 'n hewige geveg die brug herstel. Hierna kon die brug oorgesteek en die aanmars op Cassamba an Almeida voortgesit word. Na die inname van hierdie dorpe het die Suid-Afrikaanse magte opdrag ontvang om nie met die aanslag op Quibala voort te gaan nie. In Januarie het die Suid-Afrikaanse magte opdrag gekry om te onttrek en op 25 Januarie 1976 was die onttrekking grotendeels afgehandel. Burgermageenhede wat as vier veggroepe in Suid-Angola ontplooi is om die Calueque/Ruacana-waterskema en vlugtelingskampe te beskerm, het Angola egter eers op 27 Maart 1976 verlaat. Na die onttrekking van die Suid-Afrikaanse magte aan Angola in 1976, was PLAN in staat om 'n uitgebreide netwerk van opleidings- en basiskampe in die suide van Angola te vestig van waar dit SWA kon binnesvoel. Dit het dan ook in 1978 tot die eerste van 'n aantal voorsprong-operasies deur die SAW in Angola gelei. |

Operation Savannah (1975 - 1976) In 1974 the end of the Portuguese rule in Angola was already in sight. The unstable situation in Angola and the threat that the Angolan Civil War posed for SWA, led to the deployment of a South African protective force of only 2 000 men on the northern border. This force which supported the FNLA and UNITA forces, came up against a numerically superior Cuban and MPLA force but in spite of this, scored brilliant victories. In a Blitzkrieg Task Force Zulu recaptured the south western corner of Angola after Perreira de Eca, Rocades and several other towns were captured. In Central Angola Combat Group Foxbat defeated the enemy at Liumbala in October 1975. Thereafter Task Force Zulu were victorious at Cacula and Catengue. The victories at Catengue in November 1975 forced the enemy to abandon the Benguela front. Task Force Zulu and Combat Group Foxbat halted the enemy in the Santa Comba area on the Cela front and were victorious at the battle of Ebo. In Eastern Angola Combat Group X-Ray (later renamed Combat Group Orange) were also victorious at Xangongo and Luso. The victories of Task Force Zulu and Combat Group Foxbat at the battle of Bridge 14 on the central front are well known. The battle took place after the South African • Forces had advanced to Quibala. However, they had to cross the Nhia River at Bridge 14 (which had been destroyed by enemy forces) and here a group of engineers repaired the bridge while a fierce battle was raging. Thereafter the bridge could be crossed and the advance on Cassamba and Almeida continued. After the capture of these towns the South African forces were ordered not to proceed with the attack on Quibala.In January the South African forces were ordered to After the withdrawal of the South African forces from Angola in 1976, PLAN was able to establish a wide network of training and base camps in the south of Angola from where they could infiltrate SWA. In 1978 this led to the first of a number of pre-emptive operations by the SADF in Angola. |

During military operationsthe SA Medical Service endeavoured to restrict the security forces losses to a minimum

Tydens operasies het die SA Geneeskundige Diens sy deel bygedra om die veiligheidsmagte se verliese so laag moontlik te hou

|

Operasie Reindeer (1978) Toenemende terrorisme deur SWAPO weens hul maklike toegang tot Owambo oor Angola se pop suidelike grens, het Suid-Afrika genoop om tot 'n beleid van voorsprong-operasies oor te gaan. Die besluit het gelei tot 'n reeks semi-konvensionele operasies teen primere SWAPO-basisgebiede en fasiliteite in Suid-Angola. Die eerste operasie van die aard Reindeer is op 4 Mei 1978 geloods en het bestaan uit 'n lug en valskermaanval op SWAPO se belangrikste opleidings en logistieke ondersteuningsbasis by Cassinga (bekend as "Moskou") en 'n grondaanval deur 'n gemeganiseerde mag op verskeie voorste deurgangskampe in die grensgebied insluitende 'n uitgestrekte kompleks (bekend as "Vietnam") naby Chetequera, 28 km noord van die grens. Byna 1 000 terroriste het gesterf en 200 is gevang terwyl net ses lede van die veiligheidsmagte gesneuwel het. Groot hoeveelhede toerusting en voorrade is vernietig en waardevolle dokumente is gebuit. Die verlies van opgeleide personeel en die effek van die inligting wat deur die veiligheidsmagte verkry is, was 'n groot terugslag vir SWAPO waarvan hy nooit volkome herstel het nie. |

Operation Reindeer (1978) Increasing terrorism by SWAPO as a result of easy entry into Ovambo via Angola's unprotected southerly border, compelled South Africa to embark upon pre-emptive action. This desicion results in a series of semi-conventional actions primarily against SWAPO bases and facilities in South Angola. The first action of its kind - Reindeer— was launched on 4 May 1978 and comprised of an air and paratroop attack on SWAPO's most important training and logistic support base at Cassinga (known as "Moscow") as well as a ground attack by a mechanised unit aimed at the forward transit camps on the border area including a large complex (known as "Vietnam") near Chetequera, 28 km north of the border. Approximately 1 000 terrorists died and 200 were captured with a loss of only six members of the security forces. A large quantity of equipment and supplies were destroyed and valuable documents seized. The loss of trained personnel and the effect of the information obtained by the security forces was a serious setback for SWAPO from which they never really recovered. |

Giving the salute during the mechanised parade on 4 May 1988 tp commence Operation Reindeer

Die Saluut word gegee tydens die gemeganiseerde herdenkingsparade van Operasie Reindeer op 4 Mei 1988

|

Aanvaarding van Resolusie 435 (1978) In April 1978 het SA 'n gewysigde vorm van die Westerse kontakgroep se voorstelle vir SWA aanvaar. Dit het voorsiening gemaak vir 'n algemene verkiesing onder VV-toesig vir die daarstelling van 'n konstituerende liggaam as voorbereiding vir onafhanklikheid teen die einde van daardie jaar. Dit was egter onderhewig aan die voorwaarde dat eenhede van die SAW in SWA sou bly totdat SWAPO sy ondermynende bedrywighede gestaak het. Op 29 September 1978 is die Westerse kontakgroep se konstitusionele plan as die Veiligheidsraad (WO) se Resolusie 435 aanvaar. Dit het voorsiening gemaak vir die beeindiging van vyandelikhede, die vermindering van die Suid-Afrikaanse magte tot 1 500 oor 'n tydperk van drie maande en die hou van vrye verkiesings onder toesig van 'n militere en burgerlike bystandsgroep van die WO genaamd United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG). |

The Acceptance of Resolution 435 (1978) In April 1978 South Africa accepted an amended version of the Western Contact Group's proposals for SWA. It provided for a general election under UN supervision for the establishment of a constituting body as preparation for independence by the end of that year. It was, however, subject to a condition that units of the SADF would remain in SWA until SWAPO abandoned its subversive activities. On 29 September 1978 the Western Contact Group's constitutional plan was accepted as Resolution 435 of the Security Council (UN). It provided for the cessation of hostilities, a reduction of the South African forces to 1 500 over a period of three months and the holding of free elections under the supervision of a military and civil assistance group of the UN known as the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG). |

Landmine explosions indicated the increased terrorist activities of SWAPO

Die toenemende terroristebedrywighede van SWAPO is gekenmerk deur landmynontploffings

|

Operasies in Oos-Caprivi (1978) In Junie 1978 is vasgestel dat SWAPO besig was met voorbereidsels vir 'n aanval op die militere basisse by Katima Mulilo, Wenela en Mapacha. Ten einde die aanval die hoof te bied, is twee vegspanne, nl Alpha en Bravo, op die been gebring. Die aanval het op 23 Augustus begin met 'n wegstaan-bestoking op Katima Mulilo met 122 mm vuurpyle. Een hiervan het deur die dak van 'n kaserne gedring en tien soldate gedood. Na die beeindiging van 'n artillerie en mortiergeveg het die twee vegspanne die grens oorgesteek. Vegspan Bravo se teiken was 'n SWAPO-basis sowat 30 km van die grens in Zambie, maar dit is verlate gevind en die vegspan het onverrigter sake na Mapacha teruggekeer. Vegspan Alpha het daarin geslaag om die agterhoede van 'n aantal vlugtende terroriste in te haal, maar is in 'n hinderlaag ingelok. In die daaropvolgende geveg is vyf terroriste dood terwyl sowat sestig op die vlug geslaan het. In 'n latere skermutseling by 'n terroristebasis het sewe terroriste omgekom. Op 25 Augustus het vegspanne Alpha, Bravo en Charlie Papa (wat uit 'n ondersteunings-valskermkompanie, 'n kompanie van 31 Bataljon en 'n troep 140 mm kanonne saamgestel is) die grens na Zambie weer oorgesteek en na terroristebasisse by Imusho, Cinzenbela en elders opgeruk, maar almal was reeds ontruim. Die enigste noemens-waardige voorval het by Cinzenbela plaasgevind toe die plaaslike garnisoen met 'n lugafweerkanon op 'n helikopter van die Suid-Afrikaanse Lugmag losgebrand het. Dit is deur Vegspan Bravo se artillerie uitgeskiet. Die vegspanne het op 27 Augustus oor die grens teruggetrek. |

Operations in East Caprivi (1978) In June 1978 it was learnt that SWAPO was preparing to attack the military bases at Katima Mulilo, Wenela and Mapacha. To meet this attack two combat teams viz Alpha and Bravo were formed. The attack started on 23 August with a stand-off bombardment using 122 mm rockets on Katima Mulilo. One of these penetrated the roof of a barrack killing ten soldiers. After an artillery and mortar battle the two combat units crossed the border. Combat team Bravo's target was a SWAPO base camp approximately 30 km from the Zam-bian border but they found it deserted and returned to Mapacha without having accomplished this objective. Combat Unit Alpha managed to catch up with the rear guard of a number of fleeing terrorists but were enticed into an ambush. In the fighting which ensued five terrorists were killed while about sixty fled. In a later skirmish at a terrorist base seven more terrorists were killed. On 25 August combat teams Alpha, Bravo and Charlie Papa (consisting of a paratroop support company, a company of 31 Battalion and 140 mm gun troop) again cross the border to Zambia en route to Imusho, Cinzenbela and elsewhere but found them abandoned. The only worthwhile incident took place at' Cinzenbela when a local garrison fired at a South African helicopter, with an anti-aircraft gun. This was silenced by Combat Unit Bravo's artillery. The combat units crossed the border and returned on 27 August. |

The Ratel Infantry Vehicle was successfully used during Operation Reindeer in pre-emptive strikes against SWAPO bases

Die Ratel-infanteriegevegsvoertuig is met groot welslae in voorsprongoperasies soos onder meer Operasie Reindeer teen SWAPO basisse aangewend

|

Operasies Safraan en Rekstok (1979) Die volgende twee groot operasies - Safraan en Rekstok - is vroeg in Maart 1979 van stapel gestuur. Beide operasies is genoodsaak deur die teenwoordigheid van groot getalle SWAPO-terroriste in Zambie wat besig was met voorbereidsels om teikens in SWA aan te val. Gedurende Operasie Safraan wat in vier fases plaasgevind het, is verskeie SWAPO-basisse in die omgewing van Sinjembele en Njinje-bos (Zambie) aangeval en vernietig. SWAPO het wyslik besluit om nie terug te veg nie en sy basisse in Zambie' te ontruim nog voordat hulle aangeval kon word. Tydens Operasie Rekstok is terroristebasisse by Muongo, Oncua, Henhombe, Heque en elders in Angola aangeval. |

Operations Safraan and Rekstok (1979) The next two big operations - Safraan and Rekstok- were launched early in March 1979. Both operations were necessary because of the presence of large numbers of SWAPO terrorists in Zambia preparing to attack targets in SWA. During Operation Safraan, which took place in four phases, several SWAPO bases in the neighbourhood of Sinjembele and Njinje forest (Zambia) were attacked and destroyed. SWAPO wisely decided not to retaliate but to abandon its bases in Zambia before they were attacked. During Operation Rekstok terrorist bases at Muongo, Oncua, Henhombe, Heque and elsewhere in Angola were attacked. |

Infantry soldiers give cover during a minesweeping operation

Infanteriesoldate verleen dekking tydens 'n mynvee-operasie

|

Stigting van SWA Militere Skool (1979) Teen die einde van 1979 is die SWA Militere Skool gestig. 'n Aanvang is reeds gemaak met die opleiding van junior leiers wat offisiere en onderoffisiere insluit. |

Establishment of SWA Military School (1979) Towards the end of 1979 the SWA Military School was established. A start had already been made with the training of junior leaders which included officers and noncommissioned officers. |

|

Voorstelle oor 'n Gedemilitariseerde Sone (1980) Hoop vir die implementering van Resolusie 435 het vroeg in 1980 opgevlam agv 'n voorstel vir 'n gedemilitariseerde sone langs die Angola/SWA-grens tydens die oorgangstydperk voor die verkiesing onder VVO-toesig. Hoewel die detail van die Gedemilitariseerde Sone reeds in Maart 1980 geflnaliseer is, het SA daarop aangedring dat SWAPO nie toegelaat sou word om enige basisse in die noorde van SWA te he nie. SA het ook geeis dat alle SWAPO-terroriste na Angola of Zambie noord van die Gedemilitariseerde Sone moes terugtrek. Die voorgestelde VVO-mag se vermoe om vrede te handhaaf, is ook deur SA bevraagteken. Dit het tot 'n dooiepunt gelei en Resolusie 435 is nie geimplementeer nie. |

Proposals for a Demilitarised Zone (1980) Early in 1980 there appeared to be some hope that Resolution 435 would be implemented as a result of a proposal for a demilitarised zone along the Angola/SWA border during the interim period preceding the election under UN supervision. Although details of the Demilitarised Zone were finalised in March 1980, South Africa insisted that SWAPO should be prevented from having bases in the northern part of SWA. South Africa also insisted that all SWAPO terrorists should withdraw to Angola or Zambia north of the Demilitarised Zone. South Africa also expressed doubts as the ability of the UN force to maintain the peace. This resulted in a deadlock and Resolution 435 was not implemented. |

|

Operasies Sceptic en Klipkop (1980) Die volgende operasie - Sceptic - het in Junie 1980 begin as 'n blitsaanval op 'n SWAPO-basis in Suid-Angola, maar het ontwikkel tot 'n uitgebreide operasie soos meer en meer SWAPO-opslagplekke in die gebied ontdek is. Operasie Sceptic het ook die eerste ernstige botsings met die Angolese magte, FAPLA, meegebring. Gedurende die operasie het die eerste botsing met ge-meganiseerde elemente van SWAPO plaasgevind. SWAPO het sy voorste basisfasiliteite verloor terwyl 380 terroriste omgekom het. Etlike honderd ton toerusting en voorrade asook talle voertuie is deur die veiligheidsmagte gebuit. Sewentien lede van die SA aanvalsmag het omgekom. Operasie Klipkop (Junie 1980) was heelwat kleiner van omvang en het die ontwrigting van SWAPO se voorste logistieke ondersteuningstelsel ten doel gehad. |

Operations Sceptic and Klipkop (1980) The next operation - Sceptic- was launched in June 1980 as a lightning attack on a SWAPO base in South Angola but developed into an extended operation as more and more SWAPO caches were discovered in the territory. Operation Sceptic also saw the first serious clashes between the SADF and the Angola forces (FAPLA). During the operation the South African forces clashed for the first time with mechanised elements of SWAPO. SWAPO lost its forward base facilities and 380 terrorists were killed. Several hundred tons of equipment and supplies as well as many vehicles were captured by the security forces. Seventeen members of the SA force were killed. Operation Klipkop (June 1980) was a much smaller operation aimed at disrupting SWAPO's logistic and support facilities. |

Mechanised infantry returning to base

Gemeganiseerde infanterie keer terug na die basis

|

Stigting van die SWA Gebiedsmag (1980) Die eerste beduidende stap in die werklike totstandkoming van 'n onafhanklike, inheemse weermag in SWA, was die ingebruikneming van 'n nuwe uniform op 6 September 1979 wat SWA-eenhede van die van die SAW sou onderskei. Inmiddels is 'n begin gemaak met die hergroepering van bestaande eenhede om vier formasies daar te stel, nl 'n Formasie-hoofkwartierstaf, 'n Reaksiemag (konvensio-neel), 'n Areamag (onkonvensioneel) en 'n Lugmag. Wat laasgenoemde betref, sou lugoperasies nog die verant-woordelikheid van die Suid-Afrikaanse Lugmag bly hoewel voorsiening gemaak is vir 'n lugkommando-eskader bestaande uit privaat en handelsopgeleide lugbemanning. Hulle hooftaak is om die Suid-Afrikaanse Lugmag by te staan deur middel van verkennings en kommuniksie vlugte en die verskaffing van lugoperasie-offisiere vir operasionele diens. 'n Nuwe hoogtepunt is op 1 Augustus 1980 bereik met die instelling van 'n Department van Verdediging in SWA onder beheer van die Administrateur-generaal (SWA). Vanaf die datum staan alle plaaslike eenhede gesamentlik bekend as die Suidwes-Afrika Gebiedsmag (SWA GM). Die oorhoofse beplanning, skakeling en samewerking tussen die SAW en die SWA GM sou voortaan beheer word deur 'n gesamentlike komitee met die uitsluitlike taak om 'n onafhanklike hoofkwartierorganisasie vir die SWA GM te ontwikkel. Die SWA GM sou in die eerste plek verantwoordelik wees vir die finansies, logistiek en administrasie van die Gebiedsmag terwyl die SAW steeds vir die militere operasies verantwoordelik was. Die SWA GM het uiteindelik uit 'n voltydse en 'n deeltydse element bestaan. Die voltydse element bevat Staandemaglede, vrywillige hulpdienslede en dienspligtiges. Die deeltydse lede dien in die Areamag (Gebiedsbesker-mingseenhede) en die Reaksiemag (Burgermag). Die SWA GM het uiteindelik uit 'n Hoofkwartier, agt heeltydse bataljons, 27 Areamageenhede, 'n Reaksiemagbrigade, 'n Logistieke Brigade en 'n groot aantal spesialis en opleidingseenhede bestaan. Sowat 65 persent van die vegtende elemente in die operasionele gebied het uit lede van SWA GM bestaan. |

Establishment of the SWA Territory Force (1980) The first major step in the establishment of an independent territorial defence force in SWA was the introduction of a new uniform on 6 September 1979 through which SWA units could be distinguished from SADF units. A start was also made with the regrouping of existing units into four formations: a Formation Headquarters Staff, A Reaction Force (conventional), an Area Force (unconventional) and an Air Force. As regards the latter, the South African Air Force would remain responsible for aerial operations although provision was made for an air commando squadron consisting of private and commercially qualified air crews. Their main function is to assist the South African Air Force in reconnaissance and communication flights and to provide operational officers for the operational service. A highlight was the establishment on 1 August 1980 of a Department of Defence in SWA under the control of the Administrator General (SWA). From that date all the local units would collectively be known as the South West African Territory Force (SWATF). The overhead planning, liaison and co-ordination between the SADF and the SWATF would be controlled by a joint committee with the sole object to develop an independent headquarters organisation for the SWATF. The SWATF would in the first instance be responsible for the finances, logistics and administration of the Territory Force whilst the SADF would still be responsible for the military operations. The SWATF consisted of a full-time and a part-time element. The full-time element consisted Permanent Force personnel, voluntary members of auxiliary services and national servicemen. The part-time members served in the Area Force (Area Protection Units) and in the Reaction Force (Citizen Force). The SWATF eventually consisted of a Headquarters, eight full-time battalions, 27 Area Force units, a Reaction Force brigade, a logistical brigade and a large number of special and training units. Approximately 65 per cent of the combat units in the operational area were members of the SWATF. |

|

Operasies Carnation en Protea (1981) Die botsings met FAPLA in Operasie Sceptic was die voorspel tot verdere botsings gedurende Operasies Carnation en Protea in Julie en Augustus 1981. SWAPO het as gevolg van sy terugslae in 1980 sy basisse verder noord tot naby en selfs tussen die van FAPLA geplaas om sodoende aanvalle deur die SA veiligheidsmagte te ontmoedig. SWAPO se logistieke stelsel het ook feitlik onlosmaaklik met die van FAPLA verstrengel geraak. Teen die middel van 1981 het die militere situasie in SWA se noordelike grensgebied 'n ernstige wending geneem. Die stapeling van groot hoeveelhede wapentuig en die opbou van FAPLA en SWAPO-magte in Suid-Angola het 'n wesentlike konvensionele bedreiging vir SWA ingehou. In Julie 1981 het verskeie skermutselings tussen die veiligheidsmagte en PLAN voorgekom. Die bevelvoerende generaal van die SWA Gebiedsmag het op 6 Julie aangekondig dat 52 terrorists in die bestek van slegs vier dae in gevegte met die veiligheidsmagte doodgeskiet is. Hierdie skerp toename in skermutselings met SWAPO-terroriste het die veiligheidsmagte genoop om Operasie Carnation van stapel te stuur. Hoewel 225 terrorists gedurende hierdie operasie dopdgeskiet is, was dit net gedeeltelik geslaagd. Die veiligheidsmagte het nie verder as 25 kilometer noord van die grens opgetree nie, terwyl die groter terroristebasisse verder noord gelee was. In hierdie tyd het FAPLA self ook 'n meer uittartende houding teenoor die veiligheidsmagte ingeneem. Sy lug-verdedigingstelsel het 'n besliste bedreiging ingehou vir Suid-Arikaanse lugondersteunings-operasies tydens Operasie Protea. Gedurende Operasie Protea is verskeie SWAPO-basisse en bevelsposte in die omgewing van Xangongo en Ongiva deur drie taakmagte aangeval en uitgewis. Dit het op 23 Augustus 1981 begin met 'n lugaanval op 'n FAPLA-radarstasie en sleutelpunte van die Angolese lugverdedigingstelsel. Op 24 Augustus het die grondmagte se aanmars langs drie afsonderlike roetes na Xangpngo 'n aanvang geneem. 'n Gemeganiseerde mag het basisse by die dorp aangeval waar die hoofkwartier van SWAPO se noordwestelike front gevestig was. Terselfdertyd het ander elemente SWAPO-basisse suid en suidoos van die dorp uitgewis. Xangongo is ge'i'soleer en afgesny van enige moontlike inmenging deur FAPLA-magte vanaf Humbe en Peu Peu in die noordweste en noordooste onderskeidelik. Die gemengde mag van SWAPO/FAPLA-verdedigers is na 'n kort aanslag op die tenks en infanterie wat in en om die dorp ingegrawe was, verdryf. Nadat FAPLA en SWAPO uit Xangongo verdryf is, het die hoofmag oos en suid beweeg en die FAPLA-mag by Mongua uit sy pad gestoot. Die aanval op Ongiva het op 26 Augustus 1981 plaasgevind en die dorp is op 28 Augustus ingeneem nadat 'n ander gesamentlike SWAPO/FAPLA-mag wat in en om die dorp ingegrawe was, verslaan is. Verskeie Sowjet-offisiere is in hierdie geveg dood terwyl 'n Russiese adjudant-offlsier gevange geneem is. SWAPO-fasiliteite in en om Ongiva is hierna vernietig en die operasie het op 10 September 1981 ten einde geloop. Operasie Proteawas die grootste gemeganiseerde operasie deur die SA Leer sedert die einde van die Tweede Wereldoorlog. In hierdie operasie het die veiligheidsmagte tien man verloor, teenoor die meer as 1 000 ongevalle van SWAPO en FAPLA. Onder die sowat vierduisend ton toerusting wat gebuit is, was verskeie tenks en pantser-karre, 'n groot hoeveelheid lugafweer-kanonne en sowat 200 logistieke voertuie. |

Operations Carnation and Protea (1981) The encounters with FAPLA in Operation Sceptfcwere the prelude to further conflicts during Operations Carnation and Protea in July and August 1981. As a result of the setbacks in 1980 SWAPO moved its bases further north in proximity to and even among the forces of FAPLA to discourage attacks by the South African forces. SWAPO's logistic system virtually became part of that of FAPLA. In the middle of 1981 the military situation on the northern border of SWA had become serious. The stockpiling of large quantities of ammunition and the increase in FAPLA and SWAPO forces in South Angola had become a real conventional threat to SWA. In July 1981 several skirmishes took place between the security forces and PLAN. The General Officer Commanding of the SWA Territory Force announced on 6 July that 52 terrorists had been shot in contacts with the security forces in a period of four days. This sharp increase in skirmishes with SWAPO terrorists resulted in the launching of Operation Carnation. Although 225 terrorists were shot during this operation, it did not prove to be a complete success. The security forces did not operate further than 25 km north of the border while the larger terrorist bases were situated further north. At this time FAPLA also adopted a more provocative attitude towards the security forces. Its air defence system became a real threat to the South African air support operations during Operation Protea. During Operation Protea several SWAPO bases and command posts in the vicinity of Xangongo and Ongiva were atttacked and destroyed by three task forces. The operation began on 23 August 1981 with an air attack on a FAPLA radar station and key installations of the Angola air defence system. On 24 August the ground troops advanced along three separate routes to Xangongo. A mechanised force attacked the bases in the town where the headquarters of SWAPO's north western front had been established. At the same time other elements destroyed SWAPO bases south and southwest of the town. Xangongo was isolated and cut off from any possible intervention by FAPLA forces from Humbe and Peu Peu in the north west and north east respectively. The combined force of SWAPO/ FAPLA defenders were soon driven from the tanks and infantry which were dug in and around the town. After FAPLA and SWAPO had been driven from Xangongo, the main task force proceeded to the east and south driving the FAPLA force from Mongua. The attack on Ongiva took place on 26 August 1981 and the town was occupied on 28 August after a combined force of SWAPO/ FAPLA which was dug in, was defeated. Several Soviet officers were killed in this battle and a Russian warrant officer was captured. Thereafter, SWAPO facilities in and around Ongiva were destroyed and the operation was concluded on 10 September 1981. Operation Protea was the biggest mechanised operation undertaken by the SA Army since the Second World War. During this operation the security forces lost ten men against the more than 1 000 casualties of SWAPO and FAPLA. The approximately four thousand tons of equipment captured included several tanks and armoured cars, a large quantity of anti-aircraft guns and about 200 logistic vehicles.

|

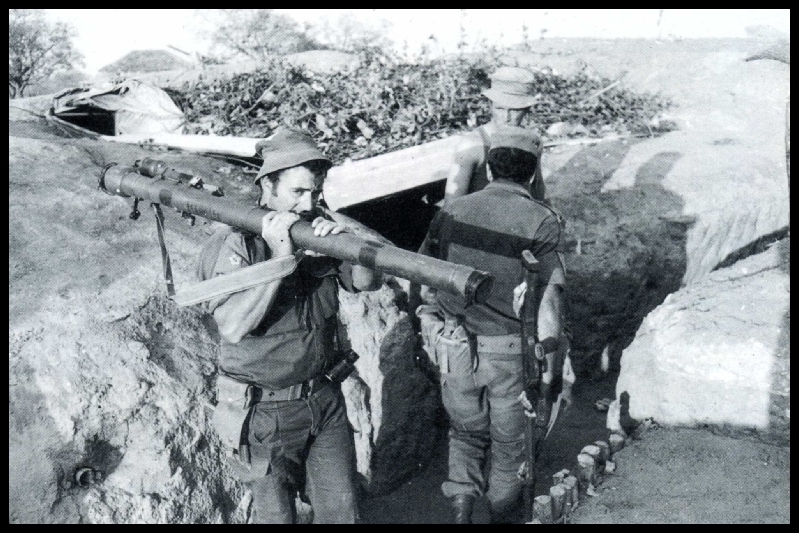

A soldier with a captured SA-7 missile launcher during Operation Protea

'n SA soldaat met 'n buitgemaakte SA-7 missiellanseerder tydens Operasie Protea

|

Operasie Daisy (1981) Operasie Protea het voortgespruit uit die inligting wat tydens vroeere operasies verkry is en het op sy beurt inligting verskaf wat gelei het tot die volgende groot operasie - Daisy- wat op 1 November 1981 geloods is. 'n Gemeganiseerde mag het tot die diepste punt sedert die Angolese Burgeroorlog ingedryf. Teikens is by Bambi en Cheraquera aangeval. Hoewel daar geen botsings met FAPLA se grondmagte was nie, het 'n paar MiG-21 veg-vliegtuie met die SA Lugmag gebots en een is deur 'n Mirage neergeskiet. Operasie Daisy is op 20 November 1981 beeindig. |

Operation Daisy (1981) Operation Protea resulted from information obtained during the earlier operations and in turn led to the next major operation - Daisy - which was launched on 1 November 1981. A mechanised force penetrated to the furtherest point ever since the Angolan Civil War. Targets were attacked at Bambi and Cheraquera. Although contact was not made with FAPLA ground forces, a few MiG-21 fighter aircraft challenged the SA Air Force and one was shot down by a Mirage. Operation Daisy was concluded on 20 November 1981. |

|

Operasie Super (1982) Vroeg in 1982 het dit duidelik geword dat SWAPO besig was met voorbereidsels om 'n nuwe front in Kaokoland te open. Verkenningselemente van 32 Bataljon is ingestuur om SWAPO-terroriste wat die gebied sou insypel, op te spoor. Sowat 250 terroriste is by 'n versamelgebied naby die dorpie lona in die suidweste van Angola aangetref van waar hulle SWA wou binnesypel. Hierna is 75 soldate na die gebied ingevlieg om 'n blitsaanval te loods. Dertig soldate is as stoppergroepe ontplooi terwyl die hoofmag van 45 man die aanval van stapel gestuur het. Ofskoon die terroriste 'n groot getalsoorwig geniet het, is hulle algeheel verras en oorrompel; altesame 201 terroriste is dood terwyl slegs twee man van 32 Bataljon lig gewond is. 'n Groot hoeveelheid ammunisie en wapentuig is gebuit. |

Operation Super (1982) Early in 1982 it became clear that SWAPO was preparing to open a new front in Kaokoland. Reconnaissance elements of 32 Battalion were sent to track SWAPO terrorists who were planning to infiltrate into the area. Approximately 250 terrorists were found at an assembly point near the little town lona in Southwestern Angola from where they intended to infiltrate into SWA. Seventy five soldiers were flown to the area to carry out a surprise attack. Thirty soldiers were deployed as stopper groups while the main force of 45 launched the attack. Although the terrorists greatly outnumbered the soldiers, they were surprised and overwhelmed; altogether 201 terrorists were killed while only two men of 32 Battalion sustained slight wounds. A large quantity of weapons and ammunition was taken. |

|

Operasie Meebos (1982) Operasie Meebos is in Julie en Augustus 1982 van stapel gestuur en het bestaan uit 'n aantal lugaanvalle op SWAPO se bevel-en beheerstelsel. Altesaam 345 terroriste is dood en SWAPO se sg "oosfront"-hoofkwartier by Mupa is vernietig voordat dit verskuif kon word. Die veiligheidsmagte het 29 soldate verloor van wie 15 in een insident omgekom het toe 'n Puma-helikopter neergeskiet en al die insittendes dood is. In Februarie 1983 het 'n Suid-Afrikaanse en Angolese afvaardiging op Kaap Verde samesprekings oor 'n voorgestelde skietstilstand gehou, dog sonder sukses. |

Operation Meebos (1982) Operation Meebos was launched in July and August 1982 and consisted of a number of air attacks on SWAPO's command and control system. A total of 345 terrorists were killed and SWAPO's so-called "east front" headquarters at Mupa destroyed before it could be moved. The security forces lost 29 soldiers of whom 15 were killed in an incident when a Puma helicopter was shot down. In February 1983 a South African and an Angolan delegation held discussions at Cape Verde on a proposed cease fire, but without success. |

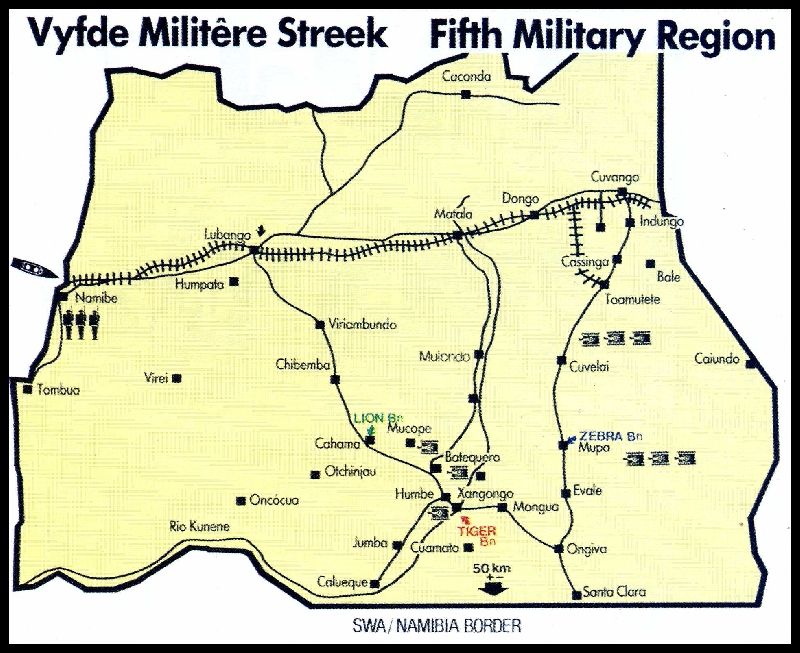

Map of the Fifth Military Region

Kaart van die Vyfde Militere Streek

|

Operasie Phoenix (1983) Teen die middel van Februarie 1983 het SWAPO 'n nuwe offensief geloods in 'n poging om sy verlore aansien te herwin. 'n Spesiale eenheid van sowat 1 700 terroriste wat in verskillende kompanies ingedeel is, het vanaf 13 Februarie begin om Owambo binne te sypel en die eerste groot kontak het op 15 Februarie plaasgevind toe vyftien terroriste dood is. Die veiligheidsmagte se teenoptredes (Operasie Phoenix) was uiters geslaagd en met die beeindiging van die operasie op 13 April 1983, het 309 terroriste reeds gesneuwel. Die veiligheidsmagte het 27 man verloor. |

Operation Phoenix (1983) In the middle of February 1983 SWAPO launched a new offensive in an effort to restore lost prestige. A special force of about 1 700 terrorists operating in different companies started infiltrating Ovambo on 13 February and in the first major contact on 15 February fifteen terrorists were killed. The security forces' counteraction (Operation Phoenix) was highly successful and at the termination of the operation on 13 April 1983, 309 terrorists had been killed. The security forces lost 27 men. |

|

Nuwe Bevelvoerende Generaal Genl maj G.L. Meiring het op 9 November 1983 die bevel van die SWA GM by genl maj Charles Lloyd oorgeneem. |

New General Officer Commanding Major General G.L. Meiring succeeded Maj Gen Charles Lloyd as SWATF's General Officer Commanding on 9 November 1983. |

|

Operasie Askari (1983) Teen die einde van 1983 het dit duidelik geword dat SWAPO besig was om 'n grootskaalse infiltrasie vir vroeg 1984 te beplan. Operasie Askari, wat hoofsaaklik gemik was op die ontwrigting van PLAN se logistieke infrastruktuur en bevel en beheerstelsel dmv verskeie lug en grondaanvalle, is op 6 Desember 1983 van stapel gestuur. Ofskoon die aanvalle op PLAN toegespits is, het FAPLA-magte in die gevegte betrokke geraak en verskeie botsings met die Angolese het gevolg. Vier gemeganiseerde veggroepe van 500 man het elk spesifieke teikens aangeval terwyl kleiner infanteriegroepe gebiedsoperasies in die grensarea uitgevoer het. Die grootste botsing tussen die SA magte en FAPLA het op 3 Januarie 1984 voorgekom toe FAPLA se 11 Brigade en twee Kubaanse bataljons SWAPO te hulp gesnel het toe sy hoofkwartier en basis vyf kilometer van Cuvelai aangeval is. Hierdie mag is egter verdryf nadat dit 324 man verloor het; die meeste van die veiligheidsmagte se 21 ongevalle in Operasie Askari is tydens hierdie botsing gely. Operasie Askari het op 13 Januarie 1984 ten einde geloop. Die SA magte se onttrekking is deur swaar reens en oorstromings vertraag. Die belangrikste gevolg van Operasie Askari was dat dit Angola gedwing het om in Lusaka samesprekings met SA te voer oor 'n staking van vyandelikhede in Suid-Angola. Samesprekings het in Lusaka plaasgevind en in Februarie 1984 is die Lusaka-ooreenkoms gesluit waarvolgens 'n Gesamentlike Monitorkommissie die onttrekking van Suid-Afrikaanse troepe uit Angola sou moniteer. Angola het onderneem dat geen SWAPO-terroriste of Kubaanse magte die gebiede wat deur die SA magte ontruim is, sou betree nie. Die onttrekking van SA magte het egter langsaam plaasgevind en kon eers in April 1985 afgehandel word. Ofskoon verskeie ontmoetings in 1985 en 1986 plaasgevind het is min vordering gemaak in die soeke na 'n vreedsame skikking in SWA/Namibie en Angola. Op 17 Junie 1985 is 'n Oorgangsregering vir Nasionale Eenheid in Windhoek ingestel. Hierdie tussentydse regering is egter nie deur die Westerse kontakgroep aanvaar nie. |

Operation Askari (1983) At the end of 1983 it became clear that SWAPO was planning a full scale infiltration for early in 1984. Operation Askari, which started on 6 December 1983, was aimed at disrupting PLAN'S logistical infrastructure and the command and control systems by means of several air and ground attacks. Although the attacks were concentrated on PLAN, the FAPLA forces became involved in the battles and several confrontations occurred with the Angolans. Four mechanised combat groups of 500 men each had specific targets to attack while the smaller infantry groups carried out area operations in the border areas. The biggest encounter between the SA forces and FAPLA occurred on 3 January 1984 when FAPLA's 11 Brigade and two Cuban battalions rushed to assist SWAPO when its headquarters and a base, situated five kilometres from Cuvelai, were attacked. This force was driven off leaving 324 dead; the highest number of losses of the security forces in Operation Askari- 21 men - was suffered in this battle. Operation Askari ended on 13 January 1984. Withdrawal of the SA forces was delayed by heavy rains and floods. The most important result of Operation Askari was that Angola was forced to discuss a possible cessation of hostilities in Southern Angola with South Africa in Lusaka. Discussions took place in Lusaka and in February 1984, the Lusaka Agreement was signed in terms of which a Joint Monitor Commission would monitor the withdrawal of the South African troops from Angola. Angola undertook to ensure that no SWAPO terrorists or Cuban forces would enter the areas from which the South African forces had withdrawn. The withdrawal of the SA forces was a slow process and was only completed in April 1985. Although several meetings took place in 1985 and 1986, little progress was made in the search for a peaceful solution in SWA/Namibia and Angola. On 17 June 1985 a Transitional Government for National Unity was formed in Windhoek. This interim government was, however, not acceptable to the Western contact group. |

Members of the JMMC at a Cuban Helicopter

Lede van die GMMK by 'n Kubaanse helikopter

|

Operasie Boswilger (1985) Na die veiligheidsmagte se onttrekking aan Angola in April 1985, het SWAPO-terroriste die situasie uitgebuit en opnuut begin om vanaf basisse in Angola oor die grens te opereer. Die veiligheidsmagte moes noodgedwonge optree. Gedurende Operasie Boswilger, wat op 29 Junie 1985 begin en slegs 48 uur geduur het is die spore van SWAPO-terroriste tot by hul basisse in drie verskillende gebiede in Angola gevolg. Op die eerste dag is 43 terroriste dood en een gevang in 23 kontakte. Op die tweede dag is veertien terroriste dood en vier gevang in 13 kontakte. Hierna het die veiligheidsmagte oor die grens teruggetrek. |

Operation Boswilger (1985) After the security forces' withdrawal from Angola on 1 April 1985, SWAPO terrorists took advantage of the situation and began to operate again across the border from bases in Angola. The security forces were obliged to take appropriate action. During Operation Boswilger, which began on 29 June 1985 and lasted only 48 hours, tracks of SWAPO terrorists bases were followed to their bases in three different parts of Angola. On the first day 43 terrorists were killed and one arrested in 23 contacts. On the second day fourteen terrorists were killed and four arrested in thirteen contacts. Thereafter the security forces withdrew. |

|

Die SWA GM in 1986 - 1987 In 1986 - 20 jaar na die aanvang van SWAPO se terroriste-bedrywighede - is 476 terroriste-voorvalle aangeteken, vergelyke met 656 die vorige jaar. Altesaam 645 terroriste is in skermutselinge met die veiligheidsmagte dood. Dit het SWAPO se totale verliese sedert sy eerste botsing met die veiligheidsmagte in 1966 op 10 283 te staan gebring. SWA GM se 61 Gemeganiseerde Bataljongroep het in 1986 twee suksesvolle militere oefeninge gehad en getoon hoekom hy deur die vyand gevrees word. Die kapelaansdienste in die operasionele gebied is in 1986 verder uitgebrei toe twee kapelane vir die eerste keer in Staandemagposte op Omega en Buffalo bevestig is. Die bevel oor die SWA GM en die SA Leermagte in SWA is op 23 Januarie 1987 deur Genl Maj George Meiring aan Genl Maj Willie Meyer oorhandig. Genl Maj Meyer was vroeer lank in SWA, toe hy die pos van tweede in bevel beklee het, voor hy in Januarie 1983 bevelvoerder van Kommandement OVS geword het. Die 1987 dienspliginname het oorweldigende reaksie uitgelok. Meer dienspligtiges as waarvoor beplan is, het aangemeld. Volgens die Hoof van Staf Personeel van die SWA GM, Brig C.C. van der Westhuizen, was die 1987 inname kwantitatief en kwalitatief gesproke die beste in vyf jaar. In Januarie 1987 het SWAPO-terroriste vir die eerste keer sedert 1983 weer in blanke plaasgebiede begin optree, maar hul bedrywighede is effektief deur die veiligheidsmagte se teeninsurgensie-operasies geneutraliseer. Dit was deels daaraan te danke dat die plaaslike bevolking die veiligheidsmagte deurentyd op die hoogte gehou het van die bewegings van terroriste in hul gebiede. In 1987 was daar meer as 2 000 gevalle waar inligting oor vyandelike bewegings, opslagplekke en wapentuig aan die veiligheidsmagte verskaf is. |

The SWATF in 1987 - 1987 In 1986 - 20 years after the start of the SWAPO terrorists activities - 476 terrorist incidents are recorded compared with 656 the previous year. A total of 645 terrorists were killed in skirmishes with security forces. The total losses sustained by SWAPO since their first confrontation with the security forces, is 10 283. SWATF's 61 Mechanised Battalion had two successful military manoeuvres in 1986 and proved why it was feared by the enemy. The chaplain services in the operational area were extended further in 1986 when for the first time two chaplains were appointed in Permanent Force posts at Omega and Buffalo. The command of the SWATF and the SA Army Forces in SWA was handed over by Major General Georg Meiring to Major General Willie Meyer on 23 January 1987. Maj Gen Meyer served previously in SWA as the Second-in-Command before he was appointed as Officer Commanding of OVS Command in January 1983. The 1987 intake of recruits caused considerable reaction. More recruits than had been planned for, reported. According to the Head of Staff Personnel of the SWATF, Brig C.C. van der Westhuizen, the 1987 intake was the best in quantity and quality. In January 1987 SWAPO terrorists were active in white farming areas for the first time since 1983, but their activities were effectively neutralised by the security forces' counter insurgency-operations. The success was partly due to the assistance of local population who kept the security forces informed of the movement of the terrorists in their areas. In 1987 in more than 2 000 instances information on enemy movement, caches and ammunition was given to the security forces. |

The G-5 gun which was used with great effect against the FAPLA forces during operations Moduler and Hooper

Die G-5 kanon wat gedeurende Operasie Moduler en Operasie Hooper met groot effek teen die FAPLA-magte

|

Operasies Moduler en Hooper (1987 - 1988) Die Suid-Afrikaanse rnagte het die UNITA-weerstands-beweging gedurende Operasie Moduler (1 Julie - 15 Desember 1987) militer ondersteun ten einde die aanmars van die FAPLA-magte op Mavinga en Jamba suid van die Lombarivier te stuit. FAPLA se suidwaartse offensief vanaf Cuito Cuanavale het op 14 Augustus 1987 met ses brigades begin. Inligting het daarop gedui dat FAPLA 'n groot aantal gepantserde voertuie rondom Cuito Cuanavale ontplooi het. 'n Suid-Afrikaanse span is tot UNPTA toegevoeg met die doel om te help in die voorbereiding van die weerstandsbeweging se tenkafweer-strategie. Die Suid-Afrikaanse magte sou ook, indien nodig, lug en artilleriesteun verskaf. Die FAPLA-magte het goeie vordering gemaak ondanks die feit dat UNITA sy logistieke ondersteuning in sy agter-hoede belemmer het. Die ontplooiing van die Suid-Afrikaanse gemeganiseerde mag het verhoed dat FAPLA die Lombarivier kon oorsteek en in hul poging om 'n brughoof te vestig, het sy brigades aansienlike verliese gely. In die gevegte op 13 en 14 September het UNITA veertig en die Suid-Afrikaanse ondersteuningsmag ses soldate verloor teenoor die 382 van die FAPLA-magte. Die ergste botsing het op 3 Oktober plaasgevind en FAPLA is 'n verpletterende nederlaag toegedien. Die oorblyfsels van FAPLA se magte het hierna by die oorblywende brigades noord van die rivier aangesluit. Hierna het FAPLA tot pm Cuito Cuanavale teruggetrek. Op hierdie tydstip was FAPLA wel nog in staat om 'n nuwe offensief te loods. UNITA en die Suid-Afrikaanse ondersteuningsmag kon dus nie terugtrek nie en opdrag is gegee dat alle FAPLA-brigades oos van die Cuitorivier vernietig of teruggedryf moes word. Hierna moes die Cuitorivier in 'n hinderlaag vir FAPLA omskep word. Voorraad-aanvulling en lugsteun van die FAPLA-magte is verder beperk en hul hoofkwartier is gedwing om terug te trek na Nancova. Tussen 9 en 16 November was die Suid-Afrikaanse mag by 'n verdere groot botsing in die omgewing van die Chambinga en Humberivier betrokke. In hierdie gevegte is sestien Suid-Afrikaanse soldate dood terwyl FAPLA 525 man en 'n groot hoeveelheid wapentuig verloor het. Operasie Moduler is teen die middel van Desember 1987 beeindig en deur Operasie Hooper opgevolg. Bykomende FAPLA-magte is na die afloop van Operasie Moduler na Cuito Cuanavale verskuif en volgens UNITA het FAPLA nou oor 25000 man beskik. Die Suid-Afrikaanse mag het G-5 kanonne effektief aangewend om hierdie sametrekking van FAPLA-magte wes en noordwaarts te verdryf. Aangesien FAPLA steeds 'n be-dreiging gebly het, het die Suid-Afrikaners UNITA bly ondersteun in sy poging om die FAPLA-magte uit die gebied tussen die Cautir en Chambingarivier te verdryf. FAPLA se 21 Brigade, wat langs die Cautirrivier ontplooi was, is op 13 Januarie 1988 uit die gebied verdryf. Daar was geen verliese aan Suid-Afrikaanse kant nie, maar FAPLA moes 'n verdere 250 man en 'n groot hoeveelheid wapentuig inboet. Op 14 Februarie is 'n aanval op FAPLA se 59 Brigade geloods en na 'n onsuksesvolle FAPLA-teenaanval, waarin die vyand onder meer 230 man en nege tenks verloor het, moes hierdie brigade terugtrek. UNITA, ondersteun deur die Suid-Afrikaanse ondersteuningsmag, het op 25 Februarie die stellings van FAPLA se 21, 25 en 59 Brigades by die Tumporivier en Dala aangeval. Hierdie aanvalle waartydens FAPLA aansienlike verliese gely het, het meegebring dat die FAPLA-magte effektief in 'n voorafbepaalde gebied by Cuito Cuanavale vasgepen is. Hierna het die Suid-Afrikaanse magte voortgegaan met 'n taktiese ontkoppeling wat reeds in Desember 1987 begin het. Die Suid-Afrikaanse magte se ingryping in Angola tydens hierdie operasies het 'n grootskaalse FAPLA-oorwinning oor UNITA afgeweer en voorkom dat SWAPO toegang tot die noordoostelike deel van SWA verkry. Die Suid-Afrikaanse taakmag se verliese was gering: 31 Suid-Afrikaanse soldate en twaalf lede van die SWA Gebiedsmag. Hierteenoor het FAPLA meer as 7 000 man en 'n groot hoeveelheid wapentuig verloor. |

Operations Moduler and Hooper (1987 - 1988) The South African forces assissted the UNITA resistance movement militarily during Operation Moduler (1 July -15 December 1987) to halt the advance of the FAPLA forces on Mavinga and Jamba south of the Lomba River. FAPLA's southerly offence from Cuito Cuanavale was launched on 14 August 1987 with six brigades. Intelligence suggested that FAPLA had deployed a large number of armoured vehicles around Cuito Cuanavale. A South African team was seconded to UNITA to assist the resistance movement in the preparation of its anti-tank strategy. If necessary, the South African forces would also provide air and artillery support. The FAPLA forces made good progress despite the fact that UNITA disrupted their logistical support in their rear areas. The deployment of the South African mechanised forces prevented FAPLA from crossing the Lomba River and in their attempt to establish a bridge head, their brigades suffered heavy losses. In the battles on 13 and 14 September UNITA suffered 40 losses, and the South African supporting force lost six soldiers as against 382 losses of the FAPLA forces. The most momentous encounter took place on 3 October when FAPLA suffered a crushing defeat. The remains of the FAPLA forces then joined the remaining brigades north of the river. Thereafter FAPLA withdrew to Cuito Cuanavale. At this time FAPLA was still in a position to launch a new offensive. UNITA and the South African supporting force could, therefore, not withdraw and orders were given that all FAPLA brigades east of the Cuitp River had to be destroyed or driven back. The Cuito River then had to be turned into an obstacle for FAPLA. A shortage of supplies and limited air support for the FAPLA forces compelled them to withdraw to Nancova. Between 9 and 16 November the South African forces were involved in a further large scale encounter in the vicinity of Chambinga and Humbe Rivers. In these battles sixteen South African soldiers were killed while FAPLA lost 525 men and a large quantity of weapons. Operation Moduler ended towards the middle of December 1987 and was followed by Operation Hooper. Additional FAPLA forces were moved to Cuito Cuanavale after the completion.of Operation Moduler and according to UNITA FAPLA then had more than 25 000 men at its disposal. The South African force successfully used G5 guns to drive off this concentration of FAPLA forces in a westerly and northerly direction. Since FAPLA still posed a threat, the South Africans continued to support UNITA in its effort to drive off the FAPLA forces in the area between the Cautir and Chambinga Rivers. FAPLA's 21 Brigade which was deployed along the Cautir River, was driven from this area on 13 January 1988. There were no losses on the South African side but FAPLA lost a further 250 men and a large quantity of ammunition. On 14 February FAPLA's 59 Brigade was attacked and after an unsuccessful counter-attack by FAPLA, the enemy lost, inter alia, 230 men and nine tanks and were forced to withdraw. UNIT A, supported by the South African supporting force, attacked the positions of FAPLA's 21, 25 and 59 Brigades at the Tumpo River and Dala on 25 February. These attacks during which FAPLA suffered considerable losses, resulted in them being pinned down in a preselected area at Cuito Cuanavale. Thereafter the South African forces continued with the tactical withdrawal which started in December 1987. The intervention by the South African forces in Angola prevented a large scale FAPLA victory over UNITA and prevented SWAPO from gaining access to the north eastern sector of SWA. The losses suffered by the South African task force were negligible: 31 South African soldiers and twelve members of the SWA Territory Force. FAPLA in contrast lost more than 7 000 men and a large quantity of weapons and ammunition. |

Three captured Russian T-54 tanks

Drie Russiese T-54 tenke

|

Operasies Packer en Displace (1988) Tydens Operasie Packer, wat Operasie Hooper in Maart 1988 opgevolg het, het 82 Gemeganiseerde Brigade (wat grotendeels uit Burgermaglede bestaan), voortgegaan om die oostelike oewer van die Cuitorivier te beskerm. Gedurende hierdie operasie het die FAPLA-magte weer eens swaar verliese gely en die situasie aan die oostelike oewer het sodanig gestabiliseer dat 'n aanvang met Operasie Displace gemaak kon word. Gedurende hierdie fase het die Suid-Afrikaanse magte aan Angola onttrek. |

Operations Packer and Displace (1988) During Operation Packer which succeeded Operation Hooper in March 1988, 82 Mechanised Brigade (which consists predominantly of members of the Citizen Force) continued to protect the eastern bank of the Cuito River. During this operation the FAPLA forces again suffered heavy losses and the situation on the eastern bank stabilised to such an extent that Operation Displace could be started. During this phase the South African forces withdrew from Angola. |

|

Konflik by Calueque (1988) 'n Gesamentlike FAPLA-Kubaanse mag het op 27 Junie eers 'n grondaanval en daarna 'n verraderlike lugaanval deur MiG-vegvliegtuie op die Calueque-waterskerna geloods. Die grondaanval is gestuit deur 'n beskermingsmag van die SAW en die SWA GM. Twaalf SA soldate en meer as 300 Kubane en Angolese het in die twee skermutselinge omgekom. |

The Conflict at Calueque (1988) A combined FAPLA-Cuban force first launched a ground attack and thereafter a treacherous air attack with MiG fighter aircraft on the Calueque Water Scheme on 27 June 1988. The ground attack was halted by a protection force of the SADF and SWATF. Twelve SA soldiers and more than 300 Cuban and Angolan died in the two skirmishes. |

|

Operasies Moduler and Hooper (1987-1988) deur Helmoed-Romer Heitman SINOPSIS: Vroeg in 1987 het inligting wat bekom is, daarop gedui dat die FAPLA-magte besig was met voorbereidsels in die 6de en 3de Militere Streke vir 'n groot suidwaartse offensief teen die UNITA-weerstandsbeweging se basisgebiede in suidoos-Angola. 'n FAPLA-oorwinning sou nie alleen UNITA 'n geweldige knou toedien me, maar ook die suidoostelike grensgebied toeganklik maak vir SWAPO van waar dit Suidwes-Afrika (SWA) kon binnesypel. Derhalwe het die RSA besluit om militer in te gryp. Gevolglik het die Suid-Afrikaanse magte die UNITA-weerstandsbeweging gedurende Operasie Moduler (1 Julie-15 Desember 1987) militer ondersteun ten einde die aanmars van die FAPLA-magte op UNITA se hoofbasisse by Mavinga en Jamba suid van die Lombarivier te stuit. Dit het aan die lig gekom dat die FAPLA-magte 'n groot aantal pantservoertuie random Cuito Cuanavale ontplooi het. 'n Suid-Afrikaanse span is gevolglik getaak om UNTTA by te staan in die ontwerp van 'n tenkafweer-strategie. Die Suid-Afrikaanse bystandsmagte moes ook lug en artilleriesteun lewer indien dit nodig sou word. Teen die middel van Augustus het FAPLA sy offensief vanaf Lucusse en Cuito Cuanavale in Angola met twee hoofmagte van stapel gestuur. Die noordelike FAPLA-magte (43, 45 en 54 Brigades) se teikens was die dorpe Cago Coutinho en Cangamba. Hoewel die drie FAPLA-brigades na die Cangamba-gebied kon deurbreek, kon hul nie verder vorder nie en moes na die gebied random Lucusse terugtrek. Die suidelike deel van die FAPLA-offensief vanaf Cuito Cuanavale is op 14 Augustus 1987 geloods. Die FAPLA-magte wat hierby betrokke was, het bestaan uit 25, 16, 21, 47, 59, 66, 8 en 13 Brigades. Die FAPLA-magte het aanyanklik goed gevorder ofskoon hul voortdurend las gehad het van UNITA-elemente wat gepoog het om hul ontplooiing en logistieke voorbereidsels te belemmer en te ontwrig. Die FAPLA-offensief het tot by die Lombarivier gevorder waar sy 47 Brigade deur 'n Suid-Afrikaanse gemeganiseerde bystandsmag gestuit is. Die FAPLA-magte is hier verhoed om die Lombarivier oor te steek en in hul poging om 'n brughoof te vestig, het hul aansienlike verliese gely. Op 13 en 14 September het hewige gevegte voorgekom waartydens FAPLA wel daarin geslaag het om die Lombarivier oor te steek en 'n UNFTA-stelling in te neem. FAPLA het egter versuim om dit verder uit te buit en hierdie brughoof is gou opgeruim. In hierdie gevegte het UNITA veertig en die Suid-Afrikaanse ondersteuningsmag en elemente van die SWA Gebiedsmag ses soldate verloor teenoor die 382 van FAPLA. Op 3 Oktober het 'n hewige veldslag gevolg waartydens die FAPLA-magte en veral 47 Brigade 'n verpletterende nederlaag toegedien is. Die oorblyfsels van sy brigades het hierna sonder hul hooftoerusting uitgewyk en by die oorblywende FAPLA-brigades noord van die rivier aangesluit. Hierna het FAPLA tot by Cuito Cuanavale teruggeval. UNITA het FAPLA se nederlaag op 4 Oktober opgevolg deur die Lombarivier oor te steek en die FAPLA-stellings langs die rivier op te ruim. FAPLA was in daardie stadium wel nog in staat om weer tot die aanval oor te gaan. Derhalwe kon UNITA en die Suid-Afrikaanse ondersteuningsmag nie dadelik terugtrek nie en opdragis ontvang dat alle FAPLA brigades oos van die Cuitorivier geneutraliseer moet word. Teen die middel van Oktober was die Suid-Afrikaanse ondersteuningsmag se G-5 medium kanonne binne trefafstand van Cuito Cuanavale en die lugbasis aldaar is afgesluit. Die G-5 kanonne is ook gebruik om FAPLA se gebruik van en beweging deur die dorp aan bande te le en om die herstel van die brug oor die Cuitorivier te voorkom. Die FAPLA-magte se voorraad-aanvulling en lugsteun is hierdeur verder beperk en hul hoofkwartier moes noodgedwonge na Nancova terugtrek. Die Suid-Afrikaanse ondersteuningsmag was tussen 9 en 16 November by hewige gevegte in die omgewing van die Chambinga en Humberivier betrokke. In hierdie botsings is 16 Suid-Afrikaanse soldate dood, terwyl FAPLA se verliese op 525 man en 'n groot hoeveelheid wapentuig te staan gekom het. Teen die middel van Desember 1987 was Operasie Moduler afgehandel en dit is deur Operasie Hooper opgevolg. Na Operasie Moduler is bykomende FAPLA-magte na Cuito Cuanavale verskuif. Inligting wat deur UNITA verskafis, het daarop gedui dat die FAPLA-magte oor 25 000 man beskik het en weer 'n offensief kon loods. Die Suid-Arikaanse ondersteuningsmag se G-5 medium kanonne het egter effektiewe vuur op die vyandelike magte afgebring en hierdie sametrekking van FAPLA-magte is wes-en noordwaarts verdryf. Desondanks het FAPLA steeds 'n bedreiging gebly en die Suid-Afrikaanse bystandsmag het voortgegaan om UNTTA te ondersteun in sy poging om die FAPLA-magte uit die gebied tussen die Cautir en Chambingarivier te verdryf. UNITA, ondersteun deur die Suid-Afrikaanse mag, het op 13 Januarie 1988 daarin geslaag om FAPLA se 21 Brigade, wat langs die Cuatirrivier (II) noordoos van Cuito Cuanavale ontplooi was, uit die gebied te verdryf. Die Suid-Afrikaners het geen verliese gely nie, maar FAPLA het 'n verdere 250 man en 'n groot hoeveelheid wapentuig verloor. 'n Aanval is op 14 Februarie op FAPLA se 59 Brigade geloods, maar die vyand het met 'n teenaanval geantwoord. FAPLA se offensief het egter misluk en dit het onder meer 230 man en nege tenks verloor. Hierna het die oorblywende elemente van 59 Brigade terugtrek. Die Suid-Afrikaanse mag het UNITA op 25 Februarie tydens aanvalle op die stellings van FAPLA se 21, 25 en 59 Brigades by die Tumporivier en Dala ondersteun. FAPLA het weer eens aansienlike verliese gely en sy magte is effektief by Cuito Cuanavale vasgepen. Hierna kon die Suid-Afrikaanse magte voortgaan met 'n taktiese ontkoppeling wat reeds in Desember 1987 'n aanvang geneem het. Die RSA se militere ingryping in Angola gedurende hierdie operasies het 'n algehele FAPLA-oorwinning voorkom. Terselfdertyd is verhoed dat SWAPO toegang tot die noordoostelike deel van SWA verkry. Die Suid-Arikaanse taakmag se verliese was gering: 31 Suid-Afrikaanse soldate en 12 lede van die SWA Gebiedsmag. Hierteenoor het FAPLA meer as 7 000 man en 'n groot hoeveelheid wapentuig verloor. |

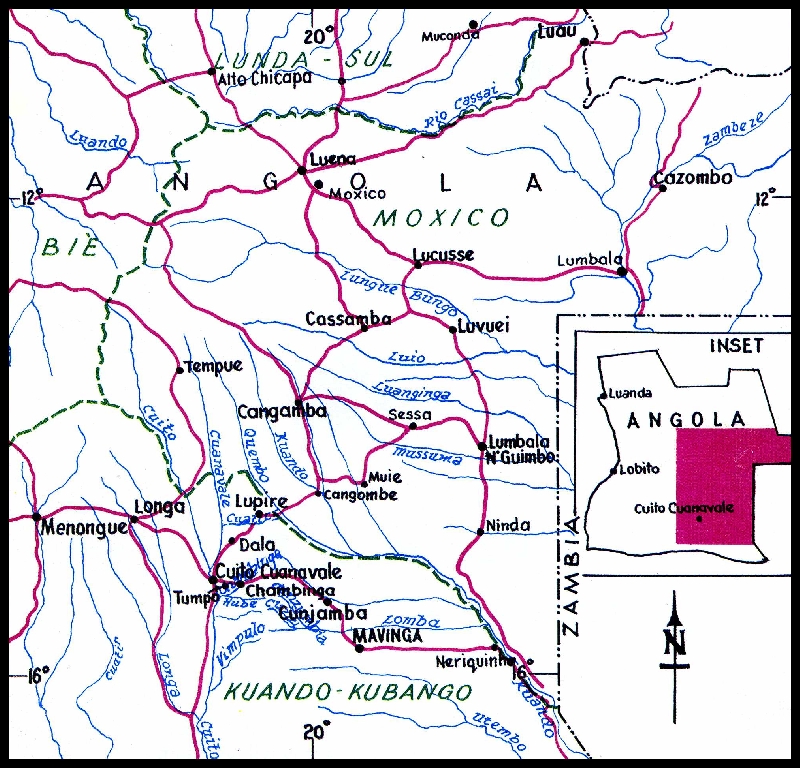

The Military regions of Angola

Die Militere streke van Angola

|

Introduction A South African mechanised force operated in support of UNITA in south-eastern Angola from September 1987 to March 1988. An element remained in Angola after the main operations ended to cover UNITA's south-western flank and to provide artillery support. The motivating factor for the mid-1987 decision to again intervene in the Angolan Civil War was intelligence showing that FAPLA was preparing for a major offensive against UNITA's base areas in south-eastern Angola. A FAPLA success here would not only weaken western-orientated UNIT A, it would open up south-eastern Angola to S WAPO terrorist operations against those parts of north-western South West Africa which have been peaceful for many years. A victory by the Soviet-sponsored MPLA forces would also increase the danger of Soviet-sponsored and perhaps Cuban-backed instability in neighbouring countries. The South African government therefore decided to commit elements of the SADF to an operation designed to prevent a UNITA defeat. This deployment peaked at around 3 000 men. The first definite indications that a major offensive against UNITA's base areas was intended, were intelligence reports of a large-scale build-up by FAPLA in the 6th and 3rd Military Regions from early 1987 onward. The movement of arms through Luanda had also reached "alarming" levels, and the delivery of some equipment by Soviet Air Force transports confirmed a keen Soviet interest in the forthcoming offensive. Another indicator of Soviet interest and support was the deployment of at least four 11-76 transport aircraft to Angola to assist with the movement of troops, equipment and supplies - even fuel - to the staging areas around Cuito Cuanavale in the 6th Military Region, and at Lucusse and Luena in the 3rd Military Region. By March 1987 there was no longer any doubt that an offensive was on the way. Intelligence analysts were by now also beginning to ascertain FAPLA intentions. UNITA meanwhile had begun a major effort to disrupt the FAPLA build-up by means of ambushes and raids in FAPLA's rear areas. The shift of UNITA's operational emphasis from expanding its area of operations to disrupting FAPLA deployment for the forthcoming offensive began in March, operations in central and northern Angola being stepped up in an effort to tie down FAPLA forces there. In July the emphasis shifted to specific operations to disrupt the FAPLA deployment and their logistic preparations. July also brought the first serious clash of the offensive. The FAPLA offensive proper began in mid-August, with two forces moving south from Lucusse and east from Cuito Cuanavale respectively. The intention appears to have been for the southward thrust to draw, fix and destroy UNITA forces outside the effective range of South African support, and to restrict the movement of supplies and replacements to UNITA forces operating in the central and northern parts of Angola. The southern force from Cuito Cuanavale would then advance to take the important air field at Mavinga, UNITA's main airhead for supplies flown in from South Africa and from the US base at Kamina in Zaire. The offensive would then continue to UNITA's headquarters at Jamba, effectively forcing UNITA back to low-level guerrilla operations, blocking easy access to supplies, and destroying much of its media image. The successful completion of this operation would also allow Angola to extend its air defence belt eastwards, complicating access by SAAF aircraft to SWAPO bases, and would give SWAPO access to virtually the full length of South West Africa's heavily populated northern regions. The initial objectives of the northern FAPLA operation appear to have been the towns of Gago Coutinho and Cangamba. UNITA "stay behind" elements successfully disrupted logistic support of the FAPLA forces approaching these towns while other UNITA elements harrassed their spearheads with artillery ambushes using light guns and rocket launchers. 43,45 and 54 Brigades reached the Cangamba area but could not make any further progress and were eventually withdrawn to the area of Lucusse. 3 and 39 Brigades were then also withdrawn, but experienced some difficulty in disengaging, at one stage being cut off. An attempt by 45 Brigade to push a supply column through to them failed with heavy losses. Both brigades did eventually succeed in withdrawing. There was no South African involvement in these operations, although a contingency plan provided for liaison teams to be despatched to the area should UNITA request assistance. These teams would then have reported on the situation and on the type and scale of assistance needed. |

|

Operation Moduler The southern element of the FAPLA offensive was launched from the area of Cuito Cuanavale on 14 August 1987. The brigades involved here were 25 Brigade, already deployed east of the Cuito River at Tumpo, and 16, 21,47, 59, 66, 8, and 13 Brigades, which were deployed for this operation. Additional forces were held in reserve. Intelligence having indicated that FAPLA had deployed a large number of armoured vehicles around Cuito Cuanavale, a team of South African officers was detached to UNITA to assist in the preparation of their anti-tank plan. UNTTA's detailed knowledge of the region facilitated a careful analysis of the likely approach routes and battlefield, and these were thoroughly prepared and mined. South Africa also agreed to provide air support if needed. In August, when the full scale of the FAPLA offensive had become clear, it was decided to also deploy South African artillery south of the Lomba River to support UNITA as needed. This deployment in support of UNITA was named "Operation Moduler". FAPLA advanced with two brigades along each of two routes: 16 and 21 Brigades from Chambinga to the source of the Cunzumbia River, southward along its eastern bank to the confluence with Lomba River, and from there towards Mavinga; 47 and 59 Brigades from the area of the sources of the Hube, Vimpulu and Mianei Rivers to the source of the Cuzizi River, southward along its western bank to the Lomba, and from there towards Mavinga. Both forces moved very slowly through often thick bush, averaging 4 km daily and generally digging in for the night around 16h00. One factor which slowed down their advance was uncertainty concerning the extent to which South Africa would support UNITA. FAPLA had already learned that South African mechanized forces move fast and strike hard, and that the SAAF's fighter-bombers are dangerous. The dangers of the sudden appearance of a mechanized force and of air attack, mandated relative concentration - both to deal with a mechanized attack and to stay within the umbrella of the accompanying air-defence systems, and the careful concealment of stationary forces. Neither requirement is conducive to fast movement in south-eastern Angola. The danger of ambush will have served to further slow the advance. Another factor was ongoing UNITA activity in the rear of the advancing forces and to the west of Cuito Cuanavale, hampering logistic support and the logistic movements of follow-on forces. As more intelligence became available concerning the strength of the advancing FAPLA force, South Africa decided to deploy a mechanized force to block the advance of FAPLA's 47 Brigade at the Lomba River. This disrupted FAPLA's planned crossing of the Lomba, various FAPLA attempts to establish bridgeheads being defeated by UNITA forces supported by SA Army and SWA Territory Force elements. 47 Brigade suffered considerable losses in this fighting. There was particularly heaving fighting on 13 and 14 September, when a FAPLA force crossed the Lomba and overran a UNITA position, killing some 40 UNITA men. FAPLA did not exploit, however, and this bridgehead was soon cleaned up. There were six engagements involving the South African force over these two days. Six South African soldiers were killed, two APCs were destroyed and two damaged in the fighting. The FAPLA force involved - an independent "tactical group" - suffered 382 men killed and lost six tanks and various other vehicles captured. Angolan claims suggest that the SAAF had meanwhile set about isolating the battlefield. Specific claims include air strikes which disrupted FAPLA attempts to move up additional forces between 20 and 30 September. No further reinforcement was attempted by FAPLA thereafter. There was a fierce clash on 3 October 1987, and this marked the turning point of the fighting. FAPLA's 47 Brigade was engaged and severely mauled, withdrawing without their main equipment in disorder during the night of 3/4 October to join up with 59 Brigade. Both brigades then withdrew to the area of their jumping-off point. 16 and 21 Brigades were also withdrawn. 47 Brigade lost 250 killed and a large amount of equipment destroyed or captured. Among the equipment losses were three SA-8 and two SA-9 launcher vehicles, eighteen tanks, three ICVs, sixteen APCs, five armoured cars, six 122 mm guns, the equipment of three light AAA batteries, and 120 logistic vehicles. UNITA followed up the defeat of this FAPLA force, crossing the Lomba on 4 October and evicting FAPLA from their positions along the River. FAPLA now adopted a defensive posture while it strove to move additional brigades into the area. 16 and 21 Brigades were deployed at the source of the Chambinga River, 59 Brigade and a "tactical group" between the Vimpulu and Mianei Rivers. By mid-October the South African G-5s had advanced to within range of Cuito Cuanavale, quickly forcing the closure of the air base. They then turned to disrupting FAPLA use of the town and movement through it, and prevented the repair of the crucial bridge of the Cuito River. FAPLA forces east of the Cuito were hit by supply shortages as a result. Air support, already severely restricted by the presence of US supplied Stingers, was now further limited, the Angolan Air Force having been driven back to the air base at Menongue, 150 km west of Cuito Cuanavale - bringing longer reaction times and less time in the target area. The shelling also forced the withdrawal of the FAPLA headquarters to Nancova on the road to Menongue. The major fighting involving the South African force was between 9 and 16 November, in the area of the source of the Chambinga and Hube Rivers. Sixteen South Africans died in this fighting. FAPLA losses to the combined South African/UNITA force were 525 killed and 33 tanks, three SA-13 launcher vehicles, fifteen APCs and 111 logistic vehicles captured or destroyed. This fighting effectively ended Operation Moduler which wound up in mid-December. |

Cuito Cuanavale and surroundings

Cuito Cuanavale en omgewing

|

Operation Hooper FAPLA had meanwhile continued to move up additional forces to the area of Cuito Cuanavale, bringing its strength there to some 25 000 men according to UNITA estimates. While this was achieved only at the expense of denuding other parts of Angola of security forces - immediately exploited by UNITA, particularly in the Cazombo salient which has again largely fallen under UNITA control, and in Cabinda - it did present the danger of a renewed FAPLA offensive before the rainy season set in. This was underlined by the deployment of Cuban troops and T-62 MBTs to the Cuito area. This concentration of forces in and around Cuito Cuanavale was promptly engaged by the G-5s which finally forced dispersion to the west and north of the town. The threat, however, remained. In the light of this continued threat, it was decided that a South African force should assist UNITA in clearing FAPLA forces from the area between the Cuatir II and Chambinga Rivers with the aim of reducing FAPLA's foothold east of the Cuito and thereby complicating a renewed FAPLA offensive. This continued deployment from 15 December was named Operation Hooper. Another element of Operation Hooper was the continued employment of G-5s to keep the air base at Cuito Cuanavale out of action, to complicate logistic movement in and around Cuito Cuanavale, and to prevent the repair of the crucial bridge of the Cuito River, thereby hampering FAPLA efforts to regain the initiative. During January the G-5s reportedly fired some 150 and 200 rounds daily at targets in and around Cuito Cuanavale. Operation Hooper proper began on 13 January 1988 with an attack on the 21 Brigade position next to the Cuatir II River to the north-east of Cuito Cuanavale. Contact with the FAPLA force was made at around 18hOO, and fighting went on for some two hours before 21 Brigade broke contact and withdrew, leaving UNITA to establish itself in the area. The South African force suffered no losses during this fighting. FAPLA losses amount to 250 killed; twelve tanks (5 of them captured), one BTR-60, two M-46 130 mm guns (captured), two BM-21s, and ten logistic vehicles (three captured). 21 Brigade regrouped at Tumpo, its original base, re-equipped and launched a counter-attack on the UNITA forces in its lost position on the Cuatir II, evicting the UNITA defenders after some heavy fighting. Other FAPLA positions east of the Cuito River were reinforced during this period. The next South African involvement came with an attack on the positions of 59 Brigade on 14 February. Fighting began around 14hOO, FAPLA breaking contact by 17h30, but counter-attacking shortly thereafter. The counter-attack failed and 59 Brigade withdrew, having lost some 230 killed. Equipment losses came to nine tanks, four BRDMs, one SA-9 launcher vehicle, five BM-21s and seven ZU-23-2 anti-aircraft guns. The South African force lost four men killed in one of five Ratels hit by direct fire during the FAPLA counter-attack. One plifant tank was disabled but came back into action later. UNITA forces simultaneously attacked 21 Brigade in its reoccupied positions, dispersing it yet again. FAPLA now withdrew 21, 23 and 59 Brigades to their logistic base at Tumpo, preparing a defensive position there. On 25 February a South African force attacked FAPLA positions south of the Tumpo River and a UNITA force supported by South African mechanized elements attacked FAPLA positions at Dala. These attacks were restricted to driving outlying FAPLA forces into the main FAPLA perimeter, the main positions not being attacked. South African losses in this fighting amounted to three killed, four plifant tanks were immobilised by mines and later repaired, and two Ratels were damaged by indirect fire. This fighting marked the end of major clashes for the time being, FAPLA forces having been driven from the critical part of south-eastern Angola and confined to the area around Cuito Cuanavale. A South African force remains deployed in the area with a covering mission, however, and President Botha has suggested that there will continue to be a South African presence in southern Angola until Cuban forces are withdrawn. FAPLA has deployed at least twelve brigades in 6th Military Region, ten of them along the axis from Menongue to just east of Cuito Cuanavale. Most of a Cuban regiment is reported to have been deployed to protect the headquarters at Nancova, which has also been given strong air defences. Another Cuban regiment may have been deployed to protect Longa. Supply convoys between Menongue and Cuito Cuanavale are escorted by elements of FAPLA's 8 Brigade but are nevertheless frequently ambushed by UNITA. UNITA, for its part, is establishing itself in areas cleared of FAPLA, and has exploited its renewed and expanded freedom of movement in south-eastern Angola to extend its operations in other parts of the country, not least along the Benguela railway and in the Cazombo salient. Observers at the Lornba River fighting reported that the South African G-5 155 mm guns were a key element in defeating FAPLA here. The G-5 proved its ability to cover a wide frontage and to reach deep into the enemy rear with considerable accuracy. The fire control system showed itself able to match the gun, allowing quick target acquisition and engagement with minimum ammunition expenditure. Available information suggests that both spotter aircraft and the South African Seeker RPV were used for target acquisition and to adjust fire. The South African ammunition also proved itself, Soviet light armoured vehicles offering little protection against the 155 mm fragments. By mid-October the guns had been moved far enough forward to strike targets in Cuito Cuanavale and force the closure of the air base there. The guns apparently opened by destroying the air base's radar and air defence systems and went on to destroy aircraft on the ground, crater the runway and generally render operations extremely hazardous. Continued shelling is reported to be keeping the air base effectively closed and to be preventing the repair of the critical bridge over the Cuito River, which was dropped by a South African "smart" weapon after, according to FAPLA, earlier haying been damaged by frogmen. While there has been no detailed public comment, the SADF is clearly very satisfied with its new artillery systems. The SA Artillery has also obviously come far in developing a new doctrine to match the capabilities of its new equipment. Given that it achieved its successes in this fighting largely with towed G-5s, it is interesting to consider how the coming introduction into service of the highly mobile G-6 SP 155 mm gun will further affect the Army's doctrine and capabilities. While the SADF has not given any details, SAAF support would appear to have consisted chiefly of battlefield interdiction, much of the close air support role having been passed to the long-range G-5s. This allowed the SAAF to minimise exposure of its small fighter fleet to the comprehensive Angolan air defence system. UNITA leader, Dr Jonas Savimbi, has also said that the SAAF was instrumental in allowing him to swiftly concentrate and deploy his semi-conventional forces to meet the FAPLA advance. It seems likely that this involved moving UNITA troops from the "northern front" in the 3rd Military Region to the defensive positions along the Lomba River in time to stop the southern arm of FAPLA's offensive there. Transport operations may thus also have been a key element in defeating FAPLA, allowing the most efficient deployment of UNIT A forces to meet and stop first the diversionary and then the main arm of the offensive. South African armour and infantry would appear to have fought with their usual verve - moving faster than the terrain would seem to allow, and delivering massive violence suddenly once in contact. Their ability to move rapidly, manoeuvre to gain the best relative position, and then to engage and destroy an enemy force in the extremely dense bush and, often, soft sand of south-eastern Angola is testimony to an exacting training system.-Visibility in some parts of the battle area is below 100 m, even less in places; the sand too soft to walk in with comfort. The toughness and reliability of the Ratel ICVs and of the Samil-series logistic vehicles is also a major factor. The Ratel-90 also appears to have again proven itself in the anti-tank role, although it was developed as a fire support vehicle and not as a tank destroyer. The Ratel-81 saw action for the first time, giving the mechanized infantry a highly mobile source of "in house" fire support. The equally new SP 20 mm AAA Ystervark celebrated its entry into service by bringing down at least one MiG-23. Operations Moduler and Hooper saw the first deployment of the Olifant MBT, which proved itself a tough and reliable vehicle able to absorb battle damage and to move through the heaviest bush. Its gun and fire control system proved more than capable of dealing with the opposing T-55s - although most engagements in the dense bush of the region were probably at too short a range to really test the fire control system. Operating in what must be prototypical "non armour terrain", the Olifant in fact proved particularly valuable for its ability to shrug off the restrictions of the heavy bush, and soft sand to get to where it was needed and to deal with the enemy. BASES:

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||